In his book, A Journey with Jonah: The Spirituality of Bewilderment, Fr. Paul Murray describes the American Trappist monk Thomas Merton as a modern-day Jonah the prophet. Like all of us, Merton suffered from “the Jonah syndrome.”

What is “the Jonah syndrome”?

Jonah ran away from God. The Lord said to Jonah, “Arise and go to Nineveh” (1:2), and Jonah paid money to get on a ship setting sail to Tarshish, the furthest known city in the opposite direction. While on board the ship, Jonah “had gone down into the hold of the ship and had lain down, and was fast asleep” (1:5).

The “understandable but desperate strategy of sinking down, as far as possible, into the stupor of sleep is, of course, simply a way of refusing to hear the voice of God, refusing to obey. I think it is no accident of grammar that our English word “disobedience” comes from the Latin obaudire (to listen), and so dis-obedience means, literally, “not to listen” (15).

This is “the Jonah syndrome” – the tendency to flee from God and take refuge in a safe, self-controlled environment.

When Jonah finally admits to the sailers the reason for the great storm, only one option is left: throw him into the deep.

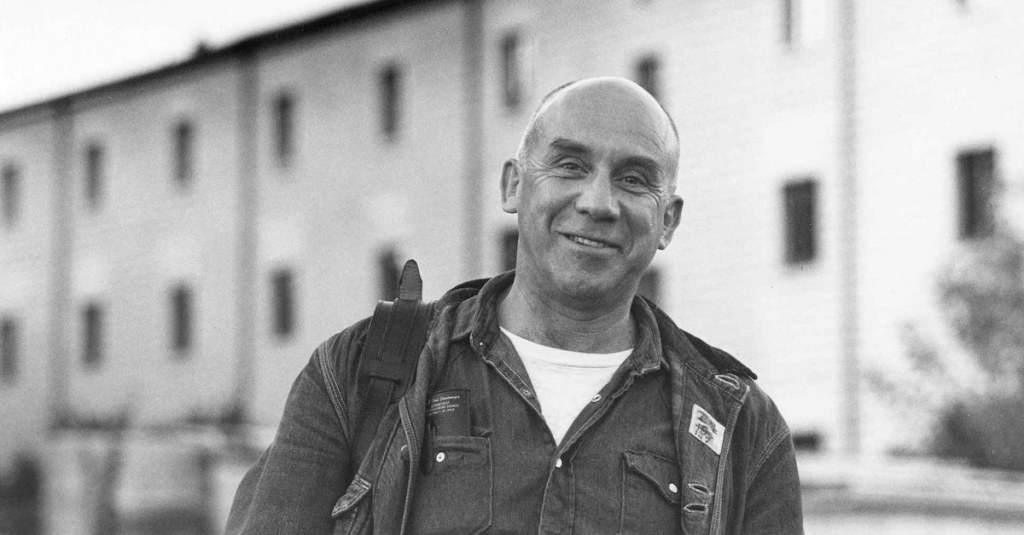

Thomas Merton and “the Jonah syndrome”

In a poem entitled, “All the Way Down,” Thomas Merton compared himself to Jonah and thus revealed his own struggles with “the Jonah syndrome” of his own life. As you read this poem, consider how honest, raw, vulnerable, and tragically real Merton is for us.

Poem: “All The Way Down”

I went down Into the cavern / All the way down / To the bottom of the sea.

I went down lower /Than Jonas and the whale. /No one ever got so far down / As me.

I went down lower / Than any diamond mine / Deeper than the lowest hole /In Kimberly / All the way down / I thought I was the devil / He was no deeper down / Than me.

And when they thought / That I was gone forever / That I was all the way / In hell I got right back into my body / And came back out /And rang my bell.

No matter how /They try to harm me now / No matter where / They lay me in the grave / No matter what injustices they do / I’ve seen the root / Of all that believe.

I’ve seen the room / Where life and death are made / And I have known / The secret forge of war / I even saw the womb / That all things come from / For I got down so far!

But when they thought / That I was gone forever / That I was all the way / In hell / I got right back into my body / And came back out / And rang my bell.

By associating himself with the prophet Jonah, Merton powerfully expressed the “paradox and bewilderment of his own life, his own vocation. Merton felt that his life as a monk, in particular, had been sealed with the sign of Jonah, that this sign had been somehow burned into the roots of his being. And why? Because he found himself, as he puts it, “traveling toward [his] destiny in the belly of a paradox.” Like Jonah, he had been ordered to go to his own Nineveh. But Merton admits: “I found myself with an almost uncontrollable desire to go in the opposite direction. God pointed one way and all my ‘ideals’ pointed in the other.”

But then Merton adds: “It was when Jonas was traveling as fast as he could away from Nineveh, toward Tharsis, that he was thrown overboard, and swallowed by a whale who took him where God wanted him to go.” So the moment of actual failure and breakdown—the experience of bewilderment in our lives—can be the moment of breakthrough, the experience of bewilderment in our lives—can be the moment of breakthrough, the moment when God’s grace finally shakes down all our defenses. And then, to our amazement, from out of the belly of failure, from out of the death of false dreams and false ideals and even from the jaws of a living hell, we can begin to experience the grace of resurrection” (30).

In this poem, Thomas Merton faces “the Jonah syndrome” head-on in a type of passion, death, and resurrection experience. Merton went down as low as possible with courage, vulnerability, and full surrender. Merton describes going down so deep that he thought he “was the devil” and others thought “he was gone forever.” And yet, at the moment of seeming despair and death, Merton “came back and rang his bell.”

Bells are an important part of Merton’s life. Gethsemani’s tower bell (where he was a monk) announces all the liturgical hours of the day. Bells call everyone to prayer and an encounter with God: “Bells are meant to remind us that God alone is good, that we belong to Him, that we are not living forth is world. They tell us that we are His true temple. They call us to peace with Him within ourselves” (Thoughts in Solitude, 67).

Treating “the Jonah syndrome” within us

When Merton says he “rang my bell,” he is truly summoning all people – including you and me – to face “the Jonah syndrome” and embark on a similar journey – a passion, death, and resurrection experience.

Here are some good questions to reflect on: What are your symptoms of the “Jonah syndrome”? What are the ways you set sail in the opposite direction from God’s will? Have you spent your time, money, and energy on the wrong things and found yourself far away from God and His will for your life? Do you feel asleep on the ship while the world is tossed in unprecedented bewilderment? Do you feel silent while the world is asking questions?

I encourage you to take these questions, and any others that might arise to prayer.

Prayerfully read through the Book of Jonah and Merton’s prayer. Give yourself permission to spend the time in prayer to go deep.

If you do, you might also experience the resurrection and be able to joyfully ring your own bells, the “bells of resurrection” you received from Christ at the bottom, who was with you every step of the journey.

Leave a comment