Preliminaries on the Spirit’s Procession

When we use the word “love” as a proper name for the Holy Spirit, rather than as a common name, we do so in order to designate a relation of origin: the Love that proceeds from the Father and the Son.

To speak about a divine person who is love as the “Holy Spirit” is fitting

The word “Spirit” denotes immateriality: we are talking about an immaterial procession analogous to the movement of love in the human person by an act of the will, the love that pertains to reason and spiritual action. Spiritual love, simply put, is a movement of the will toward the beloved.

The word “Holy,” for its part, is attributed to whatever is ordered to God: that which is “holy” is that which makes us tend toward God.

But love or charity makes one tend toward God. It is appropriate then to name the person in God who is love by a name, and the name Holy Spirit denotes the holiness of the person who is subsistent love.

What we first come to know actively, we also may come to love, and love inclines us outwardly toward that which we love, and in this sense is also relational.

In a human person, love derives from knowledge and proceeds toward the beloved. Consequently, we can understand that if the Spirit proceeds from the Father as his spirated love, he does so as one who proceeds from the Father in and from his begotten Word, according to the analogy of love proceeding from knowledge.

Aquinas expressly affirms in ST I, q. 36, a. 3, that the spiration of the Holy Spirit occurs “from the Father through the Son [a patre per filium],” which is to say, by the Father’s power received fully by the Son.

Both paternal principality:

- As the Son has his whole being precisely as Son from the Father, so too all that the Father has, the Son has received— “All that the Father has is mine” ( Jn 16:15). This eternal possession includes the reception from the Father of an eternally active role as principle in the spiration of the Spirit.

- The Son is truly and completely the principle of the Holy Spirit with the Father, but also only and always from the Father (i.e. the principality of the Father).

- This Thomistic relationalist account of the paternal principality provides a conceptual bridge between the Eastern notion of spiration through the Son and the Western notion of spiration from the Father and the Son as from one principle.

And one principle of the Father and Son:

- It is precisely because the Son receives everything that he has and is as God from the Father that he also receives from him the active power of being the eternal origin of the Spirit, with the Father, as one principle.

The Holy Spirit as Love

An analogy from human spiritual love that is relational, that is, one that implies a relation of origin, in order to speak by similitude about the Holy Spirit as a person who is love.

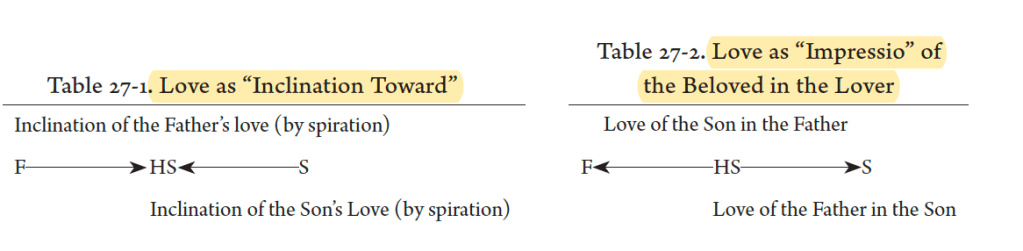

Aquinas identifies such an analogy by speaking of spiritual love in two distinct senses

- Inclination: The notion of love as an inclinatio or affectio refers to the spiritual tendency toward the beloved that is inherent in love. When one human being perceives intellectually the goodness of another, he or she can begin to love the other person by spiritual inclination or affection. This is an analogy from efficient causality, or love’s “tendency toward” the object of its love.

- Impression: The notion of love as an impressio refers to the characteristic way that love makes an impressio, that is to say, an impression or presence of the one who is loved in the heart of the one who loves. Love tends toward the good that is loved, such that the good is in a sense present to or within the one who loves. And the one who loves rests in the beloved as the immanent term of the act or movement of loving. This is the impression that the object loved makes upon the heart of the one who loves, by being present to or in the love of the lover, such that the lover rests spiritually in the beloved. This is accordingly an analogy from final causality or perfection of completed movement.

Filioque

This all being said, there is a fair amount at stake theologically, Christologically, and soteriologically in the reception of and understanding of the Filioque, as suggested first of all by the crisis that gave rise to the elaboration of this doctrine—the Arian crisis. For the doctrine in the first place makes it clear that, in keeping with scripture, the Son is truly God, and is also the Savior from whom the Spirit of salvation and divinization is sent upon the world, the Spirit by whom believers are adopted into the Father’s Spirit of Sonship.

3 grouping of scriptural texts for affirming the Filioque:

- The first grouping speaks of the Spirit of the Son: Acts 16:7 speaks of “the Spirit of Jesus”; Romans 8:9 of “the Spirit of Christ”; and Galatians 4:6 of “the Spirit of his [the Father’s] Son.”

- The second grouping includes texts that speak of the Son’s sending of the Spirit. Examples would include John 15:26, where Jesus speaks of “the Counselor [i.e., the Spirit] . . . whom I shall send to you from the Father”;15 and Luke 24:49: “I send the promise of my Father [i.e., the Spirit] upon you.”

- The third grouping consists especially of Johannine texts that speak of the Spirit as imparting what he has received from Jesus to the disciples. For example, in John 16:14 Jesus says that “he [the Spirit] will take what is mine and declare it to you,” a motif that is reiterated again immediately in John 16:15.

Aquinas’ arguments for the Filioque

- Relations of origin: The only way to distinguish the persons in the Trinity, who are each equal and identical in deity, is by relations of origin. As such, the Son and Spirit must be differentiated in their processions by a relation of opposition.

- The analogy of the Spirit as the Love of the Father: Love’s proceeding presupposes a knowledge that proceeds as word. This idea is fairly self-explanatory. Love is intelligible for us only as the love of knowledge, as love proceeding from a word. Accordingly, the Holy Spirit, proceeding as Love in person, proceeds from the Father through his Word.

- The relation between the immanent Trinity and its economic manifestation in the missions of the Son and the Spirit (their being sent into the world by the Father). The idea is the following: The missions of the Son and Spirit ad extra imply relations between the persons. Thus, if the Son sends the Spirit upon the Church—as he is depicted as doing in the scriptures—then the Spirit proceeds from the Son as a person.

Modern Ecumenical Attempts at a Comprehensive Settlement

Note that the Catholic Church does not require consent to the ideas and arguments of any particular theological school and, in this case, does not require that Eastern Churches consent to any of the models of Trinitarian life presented above as a condition for Church unity.

Consider first the Catechism of the Catholic Church’s nuanced formulation of the Filioque that specifically highlights the Father’s fontal position in the Trinity: “the eternal order of the divine persons in their consubstantial communion implies that the Father, as ‘the principle without principle’ [Council of Florence; DS 1331] is the first origin of the Spirit, but also that as Father of the only Son, he is, with the Son, the single principle from which the Spirit proceeds [Council of Lyons II; DS 850].”20 By emphasizing the paternal principality in this way, the Catechism is attempting to take careful account of traditional Eastern Christian theological concerns with the Filioque. Only the Father is the fontal principle of the life of the Trinity, and both the Son and the Spirit proceed from the Father, who is the origin of all within all.

If we begin, with the Eastern tradition, by considering the Father as the principle and unique source of the Spirit, and add to this that the Father is relative in all that he is, then we have to think about how the Father, in his spiration of the Spirit, relates to the Son, since the Father’s relation to the Son is eternally coexistent with his relation to the Spirit.

On this Thomistic relationalist account, one can hold simultaneously to a set of theologically coherent ideas: the principality of the Father, the notion that the Spirit proceeds originally from the Father as from a principle source, and the idea that the Spirit proceeds through the Son and from the Son as one principle with the Father. Far from being incompatible notions, these ideas are mutually complementary and deeply interrelated.

In his treatment of the Spirit as Love, Aquinas stresses above all love’s relational dimension, both in terms of love as an inclination toward, and as making an impression on, one’s beloved. Applied to the Trinity, this means that the Father and Son spirate the Spirit in their mutual act of love for one another, each inclining toward the other and making an impression on the other, the Spirit accordingly forming the bond of love between them. 504